Anatomy of Criticism

- Irene Banks

- May 21, 2024

- 10 min read

Updated: May 12

Book Information:

Northrop Frye

Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey

Copyright 1957

ISBN: 978-0-691-20256-3

About the Author:

From the book jacket: “Northrop Frye (1912-1991) was university professor at the University of Toronto, where he was also professor of English at Victoria College. His books include Fearful Symmetry: A Study of William Blake (Princeton).”

I first learned of Northrop Frye from reading Harold Bloom. In The Western Canon: The Books and School of the Ages, Bloom wrote: “Yet when I think of the modern critics I most admire - Wilson Knight, Empson, Northrop Frye, Kenneth Burke - what I remember first is neither theories nor methods, let alone readings. What return first are expressions of vehement and colorful personalities: …Frye cheerfully characterizing T.S. Eliot's neo-Christian account of civilization’s decline as the myth of the Great Western Butterslide...” (Bloom 179) Not only did his name intrigue me, but his sense of humor belied my image of a stuffy book critic. I made a mental note to investigate Frye more thoroughly one day. Subsequently, I started my Banks Western Canyon blog. Because I intend the blog to be a collection of book reviews, I decided to read a top book about literary criticism. A quick Google search directed me toward Northrop Frye whose slick quote had lingered in my thoughts. The internet suggested that Frye was a major influence on a generation of writers, including Margaret Atwood, an author whom I admire. When I purchased Anatomy of Criticism, I learned from the book’s forward by David Damrosch that what the internet said was true: “… Margaret Atwood would probably never have written The Handmaid’s Tale or The Penelopiad without her deep engagement with Frye’s theories of myths and archetypes.” (Frye ix)

The Author's Purpose

Northop Frye’s choice of the word anatomy in the title of his book shows his intent. The definition of anatomy is “the scientific study of the body and how its parts are arranged” and “a detailed examination of a subject.” (Cambridge Dictionary) In this case, the body is not human, but refers to the body of Western literature, primarily that written in English. His main purpose is to inform his reader. He writes, “In this book we are attempting to outline a few of the grammatical rudiments of literary expression… The aim is to give a rational account of some of the structural principles of western literature in the context of its Classical and Christian heritage.” (Frye 133) Unlike Harold Bloom’s book, The Western Canon, which is practical criticism, Frye’s book is pure critical theory. He refers to, but does not quote, specific works, nor does he proffer value judgment on them. Instead, he uses specific works as examples to demonstrate how they fit into the anatomy of literature.

Frye’s book is sweeping, and his own words about “encyclopedic” forms of literature apply to what he has achieved. In reference to myths, legend, and folk tales, Frye discusses what epic poets had to know: “Lists of kings and foreign tribes, myths and genealogies of gods, historical traditions, the proverbs of popular wisdom, taboos, lucky and unlucky days, charms, the deeds of the tribal heroes, were some of the things that came out when the poet unlocked his word- hoard.” (Frye 57) One might say the same for Northrup Frye. In a work of slightly less than four hundred pages, he packs in an encyclopedia’s worth of knowledge and thought about how all of literature, both sophisticated and what he calls naïve (popular), hangs together.

Four essays: Historical Criticism: Theory of Modes; Ethical Criticism: Theory of Symbols; Archetypal Criticism: Theory of Myths; and Rhetorical Criticism: Theory of Genres form the general structure of his views on literary criticism. He writes: “This book consists of ‘essays,’ … on the possibility of a synoptic view of the scope, theory, principles, and techniques of literary criticism. The primary aim of the book is to give my reasons for believing in such a synoptic view; its secondary aim is to provide a tentative version of it which will make enough sense to convince my readers that a view, of the kind that I outline, is attainable… It is to be regarded rather as an interconnected group of suggestions which it is hoped will be of some practical use to critics and students of literature.” (Frye 3)

Theory of Modes

Northrop Frye’s essays are dense and filled with so much information and thought-provoking ideas, that to write a thorough review of his book would require an almost book-length critique. Therefore, for the purposes of brevity, I will focus on his first essay, Historical Criticism: Theory of Modes. The Theory of Modes is based on, and advances, an idea of Aristotle’s. In Poetics, Aristotle says, “Epic poetry and Tragedy, as also Comedy, Dithyrambic poetry, and most flute-playing and lyre-playing, are all, viewed as a whole, modes of imitation. But at the same time they differ from one another in three ways, either by a difference of kind in their means, or by differences in the objects, or in the manner of their imitations.” (McKeon 624) Frye expounds on these differences. In his Theory, a mode represents “A conventional power of action assumed about the chief characters in fictional literature, or the corresponding attitude assumed by the poet toward his audience in thematic literature. Such modes tend to succeed one another in a historical sequence.” (Frye 366) He categorizes types of fiction by the protagonist’s power, which may be greater than ours, less than, or the same. The following table outlines this concept.

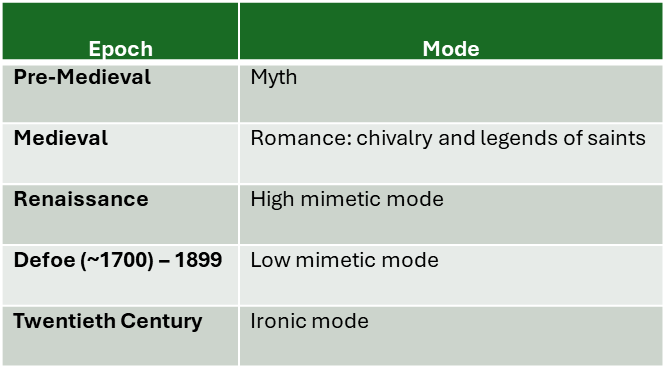

Frye argues that over the last fifteen centuries, European fiction has moved through these modes, starting with the gods and mythology, then moving to the human protagonist. The table below summarizes what he calls the five epochs which correlate to five modes. He writes comparatively little about the modes of mythology, legend, and folk tale and focuses the discussion of his Theory by starting with the Renaissance and the human leader.

Inspired by Aristotle, Frye writes at length about the concept of mimesis: “the act of representing or imitating reality in art, especially literature.” Cambridge Dictionary The High Mimetic mode is “A mode of literature in which, as in most epics and tragedies, the central characters are above our own level of power and authority, though within the order of nature and subject to social criticism. In English literature, the High Mimetic mode reaches its pinnacle with Shakespeare and Hamlet. When writers like Daniel Defoe and his Robinson Crusoe come on the scene, fiction evolves into the Low Mimetic mode which is “A mode of literature in which the characters exhibit a power of action which is roughly on our own level, as in most comedy and realistic fiction.” (Frye 366)

Further, Frye distinguishes between tragedy and comedy. Rather than simplistically meaning unhappy or happy ending, which is how we typically think of the two today; Frye refers to tragedy as fiction in which the protagonist becomes isolated from society and comedy as fiction in which he is assimilated into society. He then categorizes tragedy and comedy into modes and gives detailed examples of each type of protagonist. The tables below summarize these modes.

Tragic Fictional Modes

Comic Fictional Modes

Writing Style

By the time we reach the twentieth century, most fiction is ironic and focuses on what Aristotle called the pharmakos: “The character in an ironic fiction who has the role of a scapegoat or arbitrarily chosen victim.” (Frye 367) It is his discussion of the ironic pharmakos that allows me to transition this review from a focus on content to write about my combined fascination and frustration with Frye’s writing style. First, the frustration. His style is dense. So dense that one must often read each sentence two or three times to comprehend its meaning and even then, there is still more to analyze. For example, in his discussion of thematic irony, Frye writes, “The practice of cutting out predication, of simply juxtaposing images without making any assertions about their relationship, is consistent with the effort to avoid oratorical rhetoric. The same is true of the elimination of apostrophes and similar devices for including some mimesis of direct address.” (Frye 61) Yet simply because Frye’s writing style can be frustrating at times, does not mean that it is not worth reading. He is a writer who alternates between challenging sentences like the one above with fascinatingly readable assertions such as this one on modern-day ironic writing: “The fact that we are now in an ironic phase of literature largely accounts for the popularity of the detective story, the formula of how a man-hunter locates a pharmakos and gets rid of him. The detective story begins in the Sherlock Holmes period as an intensification of low mimetic, in the sharpening of attention to details that makes the dullest and most neglected trivia of daily living leap into mysterious and fateful significance. But as we move further away from this we move toward a ritual drama around a corpse in which a wavering finger of social condemnation passes over a group of suspects and finally settles on one. The sense of a victim chosen by lot is very strong, for the case against him is only plausibly manipulated.... In the growing brutality of the crime story (a brutality protected by the convention of the form, as it is conventionally impossible that the man-hunter can be mistaken in believing that one of his suspects is a murderer), detection begins to merge with the thriller as one of the forms of melodrama. In melodrama two themes are important: the triumph of moral virtue over villainy, and the consequent idealizing of the moral views assumed to be held by the audience. In the melodrama of the brutal thriller we come as close as it is normally possible for art to come into the pure self-righteousness of the lynching mob.” (Frye 47)

Structure and Organization

Each of the four essays contains essays within essays – a complexity characteristic of Frye’s writing style and a product of his deep knowledge of the subject matter. He writes extensively about the diagrammatic structure of critical theory. It is in this assertion where my most acute frustration with Frye lies: “Very often a ‘structure’ or ‘system’ of thought can be reduced to a diagrammatic pattern - in fact both words are to some extent synonyms of a diagram. A philosopher is of great assistance to his reader when he realizes the presence of such a diagram and extracts it, as Plato does in his discussion of the divided line. We cannot go far in any argument without realizing that there is some kind of graphic formula involved.” (Frye 335-336) Yet, ironically, Frye includes no visual or graphic tools in his own text! Therefore, reading Anatomy of Criticism is like reading an extensively detailed and descriptive book about a work of architecture without being able to see it either in the form of pictures, tables, diagrams, graphs, or other visual devices. I resorted to making tables and charts of my own which, while engaging and helpful, was also frustrating and made reading the book feel like a chore at times.

Perspective

At the start of this review, I indicated that Frye’s purpose for writing Anatomy of Criticism was to inform his reader. That bland term contrasts strongly with what he calls his introduction: “Polemical Introduction.” The definition of polemical is “a piece of writing or a speech in which a person strongly attacks or defends a particular opinion, person, idea, or set of beliefs.” Cambridge Dictionary What could there be about literary criticism that is polemical? Turns out, quite a bit from Frye’s perspective. His brilliant invective reminds me of a teacher’s reaction to Shaw’s cliché, “Those who can, do; those who can’t, teach” or to a lawyer’s reaction to Shakespeare’s line, “The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers.”

“The subject-matter of literary criticism is an art, and criticism is evidently something of an art too. This sounds as though criticism were a parasitic form of literary expression, an art based on pre-existing art, a second-hand imitation of creative power. On this theory critics are intellectuals who have a taste for art but lack both the power to produce it and the money to patronize it, and thus form a class of cultural middlemen, distributing culture to society at a profit to themselves well exploiting the artist and increasing the strain on his public. The conception of the critic as a parasite or artist manqué is still very popular, especially among artists… The golden age of anti-critical criticism was the latter part of the nineteenth century, but some of its prejudices are still around. However, the fate of art that tries to do without criticism is instructive. The attempt to reach the public directly through ‘popular’ art assumes that criticism is artificial and public taste natural. Behind this is a further assumption about natural taste which goes back through Tolstoy to Romantic theories of this spontaneously creative ‘folk.’ … An extreme reaction against the primitive view, at one time associated with the “art for art’s sake” catchword, thinks of art in precisely the opposite terms, as a mystery, an initiation into an esoterically civilized community. Here criticism is restricted to ritual masonic gestures, to raised eyebrows and cryptic comments and other signs of an understanding to occult for syntax. The fallacy common to both attitudes is that of a rough correlation between the merit of art and the degree of public response to it, though the correlation assumed is direct in one case an inverse in the other. One can find examples which appear to support both these views; but it is clearly the simple truth that there is no real correlation either way between the merits of art and its public reception… A public that tries to do without criticism, and asserts that it knows what it wants or likes, brutalizes the arts and loses its cultural memory. Art for art’s sake is a retreat from criticism which ends in impoverishment of civilized life itself. The only way to forestall the work of criticism is through censorship, which has the same relation to criticism that lynching has to justice.” (Frye 4)

Conclusion

I felt more than simply informed by reading Anatomy of Criticism. The encyclopedic nature of the book helped me create mental maps and showed me that the concepts were ones I already knew but did not have the mental imagery to be conscious of my knowledge. In this review, I have covered but a miniscule fraction of what Frye covers. I plan to use the book as a reference when I write reviews of the works from Bloom’s Western Canon. In addition to giving me foundational knowledge, I gained something else from reading Frye’s work. He wrote something that resonated with me and put into words my motivation to read the literary canon: “The culture of the past is not only the memory of mankind, but our own buried life, and the study of it leads to a recognition scene, a discovery in which we see, not our past lives, but the total cultural form of our present life.” (Frye 346)

Bibliography

Bloom, Harold. The Western Canon: The Books and School of the Ages. (#ad) New York: Riverhead Books, 1994.

Frye, Northrop. Anatomy of Criticism: Four Essays. (#ad) Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 1957.

McKeon, Richard (editor). Introduction to Aristotle. New York: The Modern Library, 1947.

Comments